One of the things I love about history is its ability to inspire. In 2016 when I signed the papers and agreed to write a book about the battle of New Market for the Emerging Civil War Series, I knew I would find inspiring stories. A short trip to the battlefield had introduced me to the accounts of the Virginia Military Institute Cadets—young men who filled a gap in the Confederate battle lines and later captured a cannon, helping turn the tide of battle. It also familiarized the story of Miss “Lydie” Clinedinst who looked after some of the wounded cadets. I felt certain there was a treasure box of inspiring material at New Market.

Jessie Hainning Rupert quickly stole my researcher’s heart, though. She stands out as an exceptional woman in New Market, though her town preferred to paint her as the villain during the Civil War. I still have questions about her life and want to pursue further research, but here is an introduction to a remarkable woman who made a significant difference in her battle-torn community, knew one of the most generals of the war, and always tried to act with kindness and moral uprightness.

On

Single

and determined to make her way in the world, Miss Hainning applied for

teacher’s positions.

In 1858,

Jessie moved about eighty miles north in the

Three

years later when the Civil War started, New Market’s men hurried to enlist or

find ways to support the Confederacy while the women made flags and participated

in other homefront activities. Not Jessie. Secession and slavery stood against

her northern and moral beliefs, and she decided to fly a

The

devoted Rebels decided to send Miss Jessie Hainning to the commander of the

Valley District for a scolding or judgment. In a surprising twist of events,

the supposedly harsh commander hurried to greet her. “Stonewall”

During

the battle of New Market on

Unable to transport all their wounded, the Union units had left behind hundreds of injured. Prejudiced and already busy looking after the Confederate wounded, the New Market citizens had little energy or inclination to care for the hurting Yankees. The Ruperts stepped in. Solomon took his wagon and hauled wounded men to the Rupert home and a nearby church, trying to get them out of the rain and elements. Jessie started coordinating efforts to get medical aid, food, and comfort for the men.

However, more wounded Yankees needed shelter. Jessie talked with her neighbors, but they refused to help. Finally, she walked into the muddy street, managed to stop a Confederate infantry column, and appealed to the captain. She provoked his compassion and humanity, and he ordered his men to tear open a nearby warehouse for temporary use as a field hospital shelter.

Jessie’s

care of the

After the war, Jessie continued to challenge her neighbors and push boundaries. Widowed in 1867, she stayed in New Market, looking for a way to support herself and her children. Her methods again caused an uproar in town. Jessie applied to the Freedmen’s Bureau and American Missionary Society, receiving funds to open a school for African Americans. On at least one occasion, she armed herself to defend her scholars from the Klu Klux Klan.

During

her later years, Jessie toured the northern states, publicly sharing about

her experiences as a Union-loyal woman in a Confederate town during the Civil

War. She attended veteran reunions and stayed in contact with members of the

34th Massachusetts Regiment. Jessie Hainning Rupert died in 1909. She was

buried beside her husband in

I have studied numerous civilian and soldier accounts from the Civil War, and I am convinced one of the most inspiring is the moment when Jessie Rupert stopped the Confederates in the New Market street. Of course there are no photographs of the moment, but it does not seem wrong to imagine the scene.

Mud. Perhaps her bloodied sleeves and skirt. A weary officer. Wounded Yankees perhaps in view and exposed to the weather’s elements. She did not shout. She did not march onto a battlefield. She made an appeal. She stepped into public view along or in that street. She asked an enemy officer to aid his fallen foes. She won a victory - a victory in the face of a hostile local community. A victory to save lives.

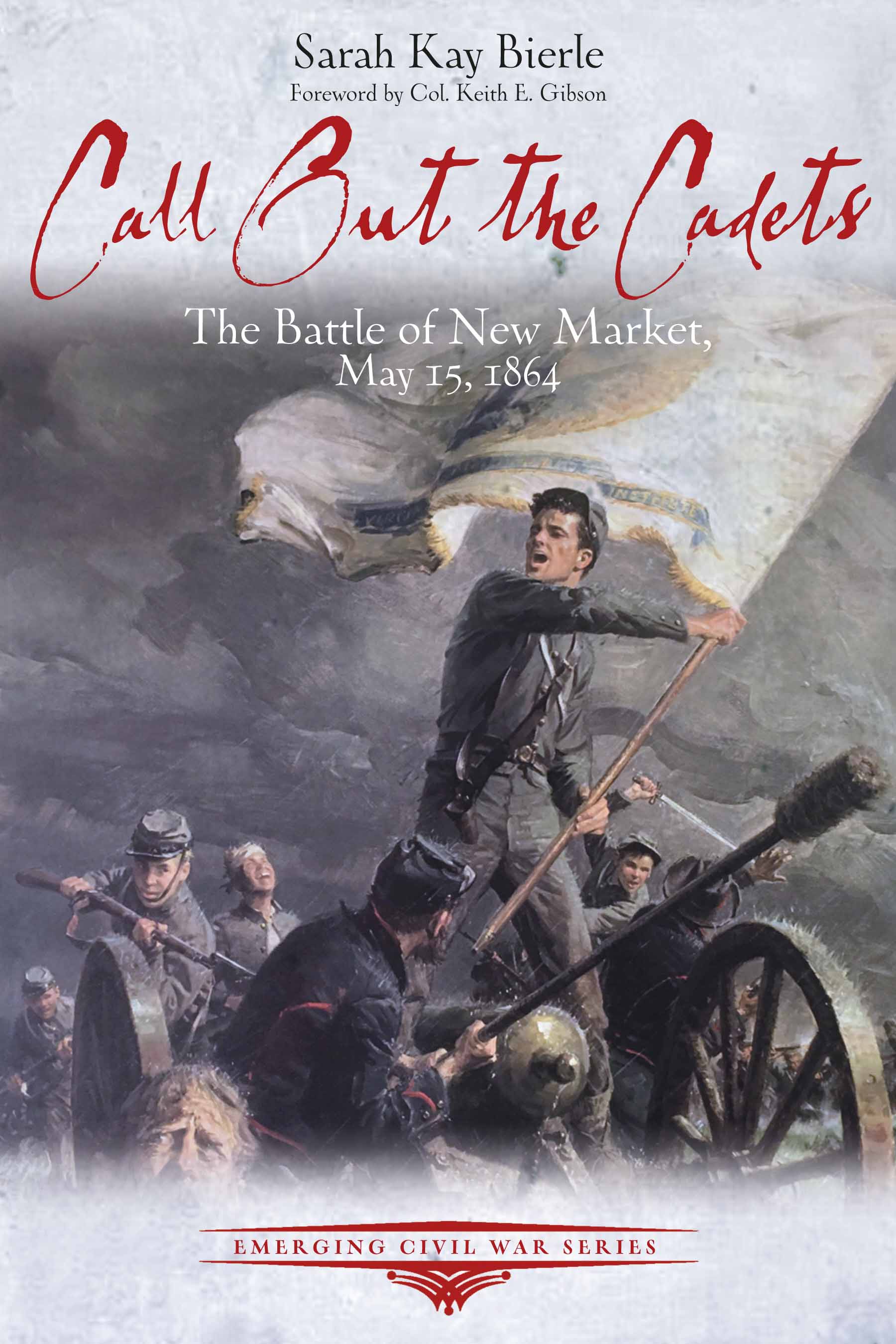

She inspires me. And I feel privileged to tell her history and include notes to visit the locations of her New Market homes and grave site in the Emerging Civil War Series book Call Out The Cadets. Alongside the military history accounts of generals, common soldiers, and cadets, one brave, loyal Union woman created her own place in New Market’s battle and community history.

-Guest blog post by Sarah Kay Bierle

Visit the Savas Beatie website or give us a call to order your copy of Call Out the Cadets by Sarah Kay Bierle